For several years, I worked as a junior doctor at Great Ormond Street Hospital, a famous children’s hospital in London. It was at this hospital that I first became interested in rare diseases, and went on to specialize in clinical genetics. Over the next 20 years, I worked with rare disease patients, particularly children, and their parents.

These parents needed to know what was happening to their child and what their child’s future would look like. Even as an experienced clinical geneticist working in a specialist London hospital, it wasn’t always easy to give people the answers they needed.

As a doctor, it’s impossible to take home every case, but of course, some stay with me so many years later. One little girl was only 6 months old when I first met her and her family. She had a particularly unusual combination of symptoms. It wasn’t until she was 6 years old that we identified her underlying condition. Giving her parents an explanation, that their daughter’s condition was called Malan Syndrome, was one of the most memorable moments in my career.

Initiating a life-changing diagnosis

A diagnosis is so important. For some patients, it’s a gateway to treatment. In the UK, having a diagnosis can also unlock access to therapies and educational, psychological, and financial support.

For parents, a diagnosis can end years of uncertainty and provide enormous emotional relief. Living with an unanswered question can be all-consuming. The diagnosis helps them find other parents, support groups, patient associations, and the correct information.

In one of life’s strange turns, I found myself on the other side of the consulting table when my daughter was diagnosed with 2 unrelated rare diseases. The hundreds of encounters I’d had with parents, witnessing the pain of their uncertainty and fears for the future, could not have prepared me for experiencing this myself first-hand.

Now, as Medical Director of Rare Diseases at Ada, I’m able to help decrease the time to a diagnosis for people with a rare disease and their carers, accelerating the support that is essential to move forward with life. It feels good to amplify the effects of my clinical experience through a digital solution that can help millions of people at the same time.

Disease modeling for biliary atresia

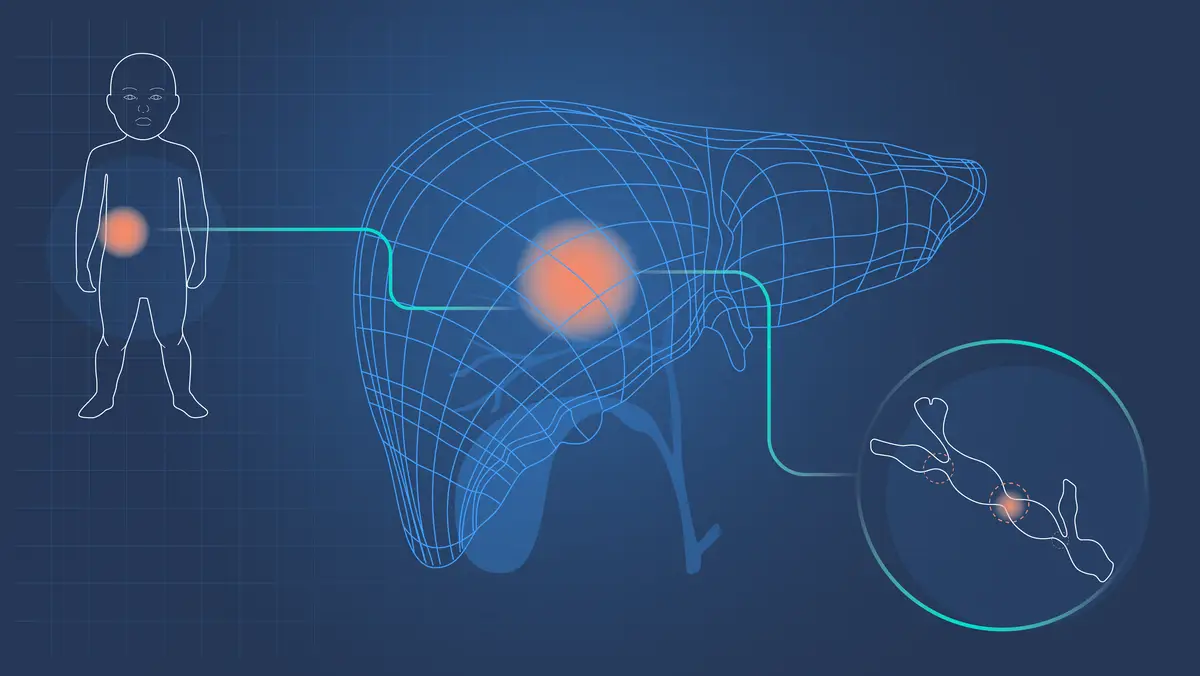

When I started as a junior doctor on a pediatric liver ward, one of my first patients had a rare liver disease, biliary atresia (BA). I’d like to share how we’ve taught Ada to detect it.

1. Identifying the need and potential

Detecting rare starts with identifying which new conditions to add to our medical knowledge base. BA affects 1 in 12,000 live births in Europe. 1 Statistically, it’s a rare disease, yet it’s the most common cause of end-stage liver disease and liver transplants in childhood.

Diagnosis of BA can be difficult because of the timing of symptom onset, and the overlap of symptoms with more common conditions. But a timely diagnosis is critical. Earlier treatment correlates with delayed or reduced need for liver transplantation. 2 Therefore, the potential to aid early diagnosis means it’s an effective disease for us to focus on.

The ability to learn from patient-reported symptoms also makes it suitable. With BA, many of the symptoms become apparent to parents within the first few weeks of life.

2. Researching the disease

Our medical doctors are trained to create disease models. They start by reviewing the scientific and medical literature to understand the natural history of a disease. They study its variations, causes, risks, presentations, epidemiology, etiology, and differentials. We also rely upon our life science partners’ disease-specific expertise to integrate clinical insights that may be unavailable in the published literature.

BA affects females slightly more often than males, is more common in Asia, and can occur by itself or can be associated with other congenital problems. In babies, the clinical triad of jaundice, pale stools with dark urine, and an enlarged liver are characteristic. Untreated, babies go on to develop symptoms of liver failure.

3. Inputting data

The collated data is added to Ada’s medical knowledge base and probabilistic reasoning engine using proprietary data tools and an ontology system that manages the many layers of information we use. This creates information that is both machine-readable and human-readable. Our disease models are the basis for Ada’s AI which guides users through a dynamic question flow, resulting in tailored symptom assessments and condition suggestions.

4. Testing and peer review process

Our thorough testing and evaluation process ensures safe and medically sound performance before a disease model is released into Ada. This is achieved using clinical cases created and tested by in-house and external doctors.

5. Releasing into Ada

Since its release, BA has been suggested as a possible cause of symptoms for 83 people across 30 countries.

Supporting better health outcomes

Earlier detection of BA has significant implications for prognosis. If a parent assesses their child’s symptoms with Ada and BA is a suggested condition, they can take the assessment report, in their own language, to a healthcare professional. This can prompt appropriate clinical investigations. The chances of successful surgery for BA, the Kasai procedure, decrease as the age at the time of surgery increases, so the younger the better. 3

Part of the reason I joined Ada is because of our ability to change lives. A study published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases showed Ada has the potential to halve the time it usually takes to get the right rare diagnosis. 4

We can’t do this alone, and work closely with clinicians, patient groups, researchers, and life sciences partners to help build out new models and raise awareness of under-treated diseases.

We are actively seeking innovative life science partners who are committed to cutting the time to a correct rare disease diagnosis to accelerate Ada’s impact.

If that’s you, please get in touch.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. “Biliary Atresia.” Accessed March 23, 2021

- Harpavat, S. et al. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, (2018), doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001887

- Chardot, C. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, (2006). doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-28

- Ronicke, S. et al., Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, (2019), doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1040-6